Sunday, August 28, 2011

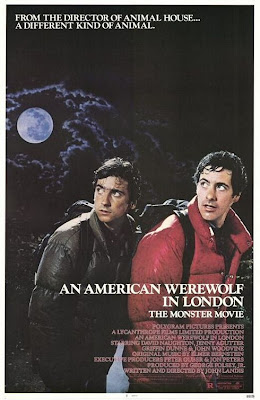

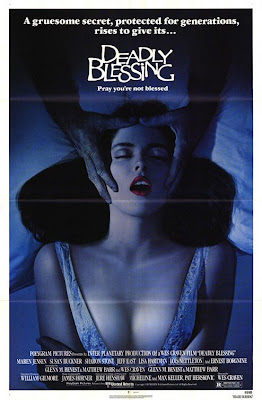

Posterized: Now Playing August 1981

Monday, August 22, 2011

The Quixotic Foibles IV: The Quest for Peace (of Mind)

The first part of my quixotic journey to attempt to get through all my unwatched DVDs and Blu-Rays is here, part II here and part III here.

The first part of my quixotic journey to attempt to get through all my unwatched DVDs and Blu-Rays is here, part II here and part III here. Funny, I thought I'd really cut down on purchasing, but alas, that is not the case. Some explanation, since the last update I've had a birthday, went on one rampant Swapadvd trade session, there was one of those Barnes and Nobles' Half-Off Criterion titles sales, as well as a Amazon's Half-Off Criterion titles sale..not to mention, uh, Criterion's Half-Off Criterion titles sale, and two or three Pasadena Swap meet visits.

So the foibles keep getting quixoticer, I guess.

Here's the DVDs or Blu-Rays I actually did make it through (I will link a review if I have written one):

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

The Dogs of War (1981, John Irvin)

In an early scene in The Dogs of War (1981, John Irvin), mercenary soldier Jamie Shannon (Christopher Walken) opens the refrigerator in his rundown one room New York apartment to reveal its major contents: a six pack of Budweiser and a small handgun. A few moments later, we see that Shannon has another gun hidden in his nightstand. These little touches are indicative of the detailed study of the world weariness and paranoia of a man who has dedicated his life to battle. The type of man who after his cover (as an ornithologist) is blown spying on an Idi Amin like dictator in the small (fictional) African nation of Zangaro and is beaten within an inch of his life, does not bat an eyelash at returning to the nation and expelling their leader, not as a revenge ploy, but rather it’s a job, nay, it’s his nature. Sure he may talk about living the quiet life in Colorado to his estranged wife (JoBeth Williams), but she’s not buying it, and neither is he probably.

Like the last film I reviewed as part of the 1981 Project, Walter Hill’s Southern Comfort, Dogs of War deals with the fallout of the Vietnam War without ever explicitly referencing the actual conflict. My blogging friend, Leopard13 (of It Rains…You Get Wet) made a salient comment about how in 1981, with the newly elected Ronald Reagan, a sense of wanting to ignore the pessimism that divided the country during the 60’s and 70’s was evident, to the point that it subconsciously led people to ignore art that dealt with Vietnam, even if, like Southern Comfort, it was on a more metaphorical level. Ironically, by the mid 1980’s, cinemas would be inundated with films (and even the television series,Tour of Duty) that focused specifically on the war itself, including the Oscar winning Oliver Stone film Platoon (John Irvin would contribute to this wave with 1987’s Hamburger Hill), but I guess that’s the nature of people’s statute of limitations on devastating and divisive affairs (probably why it took five years before any films addressing the September 11th attacks were produced and why films set in Iraq constantly fail box office wise, but I digress). The film though that Dogs reminded me most of is another Best Picture winning film, Kathyrn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker. Like that film, Dogs is a character study of a man for whom war has become not only his definition, but an addiction. And like any addict, they resist the urge and rebel, and are not blind to the fact that they’re basically a pawn in a larger machine. There’s a nice differentiation between two of his mercenary gang that Shannon attempts to recruit for the Zangaro mission. Terry (an early role for future Al Bundy, Ed O’Neill) is happy with what he earns from his job as a mechanic and gives a flimsy excuse related to the health of his sister for sitting this one out, while Drew (Tom Bergenger) quickly joins in despite his wife’s pregnant state, telling Shannon “I don’t want to stick around and see her get fat”.

Adapted from a Frederick Forsyth novel by screenwriters Gary DeVore and George Malko, the film's narrative structure is split into distinct components, with each given its own identity by director Irvin and cinematographer Jack Cardiff (who himself has directed a mercenaries in African film, 1968’s Dark of the Sun). After a tense and exciting opening tease that shows Shannon and his mercenaries escaping from a mission in Central America, the film shifts to America, where as previously mentioned, Shannon attempts to adjust to the tedium of everyday life. The next section is his undercover work in Zangaro which ends with his torture, then back to America and an attempt at the reconciliation with his wife. The next section, the recruitment and procurement of weapons and travel to Africa, has the feel of a John LaCarre spy novel, emphasizing the unsexy wheeling and dealing side of the process. For the final act, the invasion, we return to the exciting action tropes from the opening scenes. With a lot of globetrotting this narrative technique gives the film a unique spy/war film hybrid sensibility.

Director John Irvin will never be confused for an auteur by any stretch of the imagination (I just recently watched his other 1981 release, Ghost Story which is awkward and lacking of any tone), but he rises to the occasion here with tight pacing that manages to fit in a bunch of small character moments, and an epic feel for a film that only runs about 105 minutes. There may be a few dramatic moments that don’t carry the oomph they’re supposed to, but those are the exception. And Irvin excels in the film’s final fiery violent battle sequence which manages to portray a chaotic scene clearly to the viewer. The violence is loud and quick, belying Irvin’s experience as a War cameraman (as much as a person whose never been in battle can judge the verisimilitude of it).

I am not sure what its reputation was upon release, but I don’t really come across people discussing The Dogs of Warmuch today. It’s not an impeachable classic, and Walken’s performance is very similar to his work in 1978’s The Deer Hunter, but it’s sneakily powerful, as it not only addresses the role of a soldier for life, but the consequences when said soldier questions the logic of the War Machine. Sure, the African country and leader in the film may be faux and the organization Shannon works for is never specified, but it doesn’t take much to delineate the actual persons and places being protected here.